Obsidian and Bear: My-Two App Note Taking System

For years, I tried to find a single note application "to rule them all".

For years, I tried to find a single note application "to rule them all". But, after much trial and error, I have settled into a two-app note-taking system on my Mac. In a nutshell, I now use Obsidian for all my "deep research" notes, and Bear for just about everything else.

Picking a note-taking app and developing your own system is a highly personal decision. There are many excellent note applications these days, and there is no shortage of tutorials on various workflow options. I have no idea if my current setup matches your needs, but here's how I landed on my current system. I hope it provides some inspiration for your own experiments.

Obsidian

First up, in July 2020 — remember July 2020? — I read How to Take Smart Notes by Sönke Ahrens. This a real gem of a book, and the single best description of Zettlekasten I have read. It remains one of my favorite books. The book also convinced me that Zettlekasten is less about the software you pick and more about the process you use.

In particular, Ahrens is a firm believer that the act of writing is the single best way to think and learn:

We tend to think we understand what we read — until we try to rewrite it in our own words. (Source: Sönke Ahrens, How to Take Smart Notes).

If you take nothing else from the Zettlekasten process, it is this. The idea is to continually write new notes in your own words, and connect related ideas. After a few months or years, you will build up a deep network of ideas that you can continuously dip into, explore and add to.

After reading Ahrens's book, I discovered Obsidian, and I was hooked. I have been happily adding to my Obsidian vault since then.

Fast forward four and a half years, and I now have over 1,100 markdown files in Obsidian. Whenever I read scientific papers or new books, I squirrel ideas away into Obsidian.

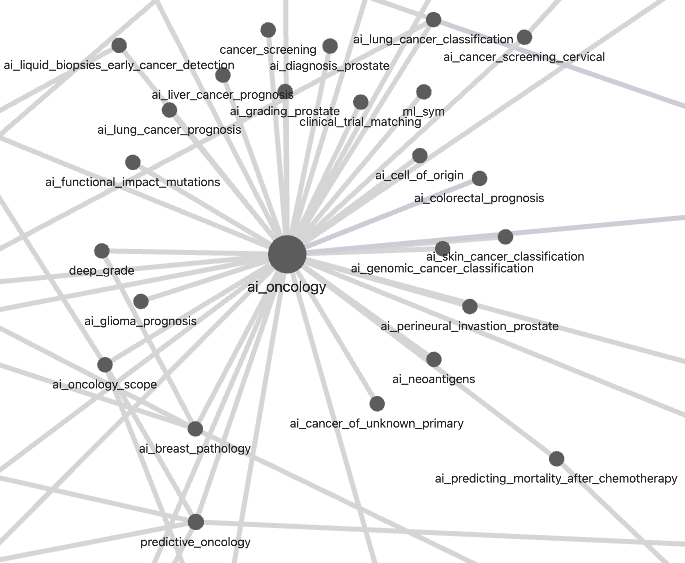

As a prime example, I spent most of last year working on a review paper of AI in oncology. This is a huge topic, and I probably read over 200 papers for that one review. All of them were processed through Obsidian. Here’s a snapshot of these notes, as shown in Obsidian’s graph view:

Honestly, I loved every minute of it.

I was able to read widely, learn new topics, connect ideas, and not get completely overwhelmed with the volume of new material. With Obsidian, I was also able to see both the forest and the trees, giving me the confidence to put my thoughts into writing.

I now consider my folder of Obsidian markdown files the single most important folder on my laptop. If it were to disappear, I honestly don't know what I would do. That's why I now keep it backed up in two spots, one locally and one in the cloud.

Bottom line: research notes go into Obsidian. I have no plans to ever leave the app. But, should Obsidian suddenly disappear, I have a folder of Markdown files that I can easily port over to the next app.

Bear

Beyond research notes, most of us have many other notes we keep track of — work projects, home projects, travel planning, personal reference items, etc.

Ahrens refers to these as "fleeting notes".

While he doesn't exactly tell you how to manage these notes, he makes a strong case that these fleeting notes should be kept separate from your permanent notes, and should not clutter up your Zettlekasten.

I ignored Ahrens's advice for a while and started adding project notes directly to my Obsidian vault. And, yes — everything became too cluttered, and I eventually reversed course. I also tried a separate Obsidian vault just for work projects, but this just didn't work for me — Obsidian is too ingrained in my brain as a research tool, and projects require a different mindset.

I realize that some folks now put everything into Obsidian. Some have even managed to put their entire lives into the tool. For example, see LifeHQ.

But, this just never worked for me. I consider my Obsidian folder my "forever notes". These are ideas and notes that I plan to keep adding to over years, hopefully decades. And, I want to keep them separate from everything else.

For a while, I tried putting all my non-research notes into Apple Notes. This seemed like a solid (and free) decision, but I don’t enjoy Apple Notes as much as Obsidian.

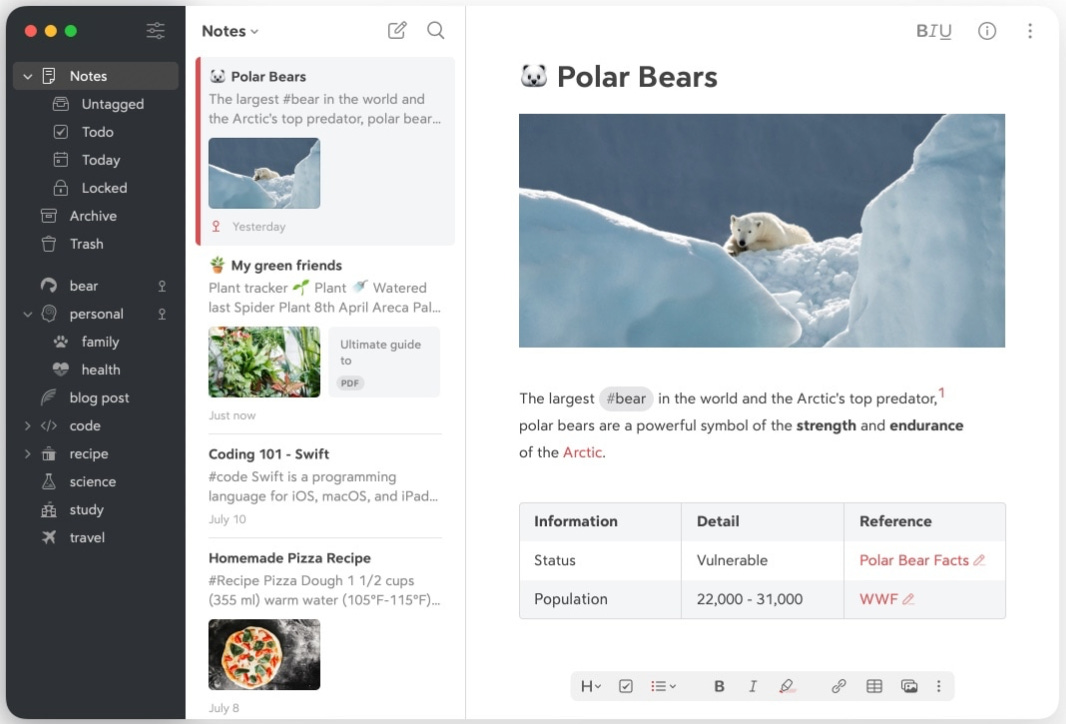

Enter Bear. I tried it for a few days, and I was hooked.

Part of the reason is that the Bear interface is elegant and spare, and a delight to use.

Bear also has three killer features for me.

First, it has native support for Markdown, just like Obsidian, and unlike the rich text format of Apple Notes.

Second, it integrates nicely with Drafts. For reasons that still confound me, Apple has walled off Apple Notes from other apps and makes integration with Drafts very sub-optimal.

Third, I like the way Bear supports tags and sub-tags. I tend to think of my research notes as a complex network of nodes. But, projects tend to be hierarchical. This is also why Tiago Forte recommends that you organize project notes into folders, which enables browsing of notes:

Browsing allows us to gradually home in on the information we are looking for, starting with the general and getting more and more specific. This kind of browsing uses older parts of the brain that developed to navigate physical environments, and thus comes to us more naturally. (Source: Tiago Forte, Building a Second Brain).

In Bear, sub-tag support gives the illusion of having folders, which taps into our spatial brains. Plus, Bear makes this even more enjoyable as you get to pick your own icons for any tag or sub-tag.

As an example, I currently work on a project called the Human Tumor Atlas Project or HTAN. The project has hundreds of collaborators and dozens of moving parts. As I have used Bear, I have organically organized all my notes via subtags, where each subtag represents a different moving part:

If I need a refresher on our plans for single-cell data modeling changes in HTAN, I just click #htan/single_cell, and it feels as if I have physically walked into a workspace dedicated to just this topic. Everything is nicely organized and ready to go.

For all these reasons, Bear just clicked for me, and it's now my go-to application for project and personal notes. As with Obsidian, I am also comforted that if Bear ever goes under, I can easily export everything to markdown and seamlessly move on.

So, that's it. Research notes go to Obsidian. All other notes go to Bear. And, both apps are a true joy to use.

Links

I will add that there is one final piece of the puzzle. I occasionally need to link from Bear to an Obsidian note. This is extremely easy — just right-click on a note in Obsidian, select Copy Obsidian URL and paste it into Bear.

I also frequently need to link from Bear to a regular file, such as a Word document or a PowerPoint deck. For this, I use Hookmark. I found out about Hookmark via a subreddit, and oh my goodness, you must use it! It enables you to create a persistent, unique link to any file on your computer or even any specific email. You can then paste this link directly into Bear, and pull up the file immediately. It works even if you move the file. I have no idea how it works, but I now use it all the time.

I am very curious to hear how others have solved these challenges. Are you all in on Obsidian? Have you devised a different hybrid system? Let me know in the comments below.